International Journal of Education & the Arts | |

Volume 3 Number 6 |

December 23, 2002 |

|

An Ethnographic Exploration of Children’s Drawings

of

|

|

Abstract This ethnographic study explores what some children in Poland represented in drawings of their first Holy Communion, how they developed them, and the significance of the drawings. We describe, analyze, and compare drawings as a whole and with findings from other studies on child artmaking. Description includes the Holy Communion experience in general, the ritual in Poland, the Corpus Christi procession, the school context and related lesson. Analysis focuses on theme, schema, color, and space usage. Drawings do not express content--deep religious feelings but reveal other aesthetic interests in massive churches and decorative details. Conclusions include summary of elements of the event's uniqueness, discussion of what was left out of the drawings, and alternative explanations which include limited drawing abilities, gender differences, outside influences, power relations, ritualistic role of the ceremony, and the essence of holy communion and the children's drawings. |

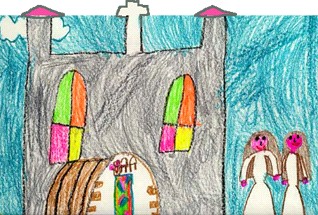

Figure 1. Jendrek's drawing of his First Communion

“I appreciate the big cross in front of our church, a big triangle. I notice the unusual shells that contain holy water. I admire the wood carvings of the Stations of the Cross and colorful stained glass windows around the saint's big altar, the golden chalice, flowers, bells, and candles,” explained Jendrek.

“My church in Zielonka is very big and slender. It looks like hands put together for praying. The arched entrance door has a big black hinge. I like the arched stained glass windows with the portraits of the saints and the big painting of Jesus with some beams flashing from his heart. At the altar is a huge [Paschal] candle, a golden calyx [chalice] and the host lifted by Priest,” reported 6-year-old Agnieszka.

“I like my church very much—the altar with candles on it and the little golden house [tabernacle] where Jesus lives, the painted sculptures of saints, the colorful stain-glass windows, two huge towers, the huge entrance door with pictures [bas-relief], and the big door handle,” described Ania.

In the above responses, Polish children revealed their admiration for their Roman Catholic churches and their accouterments. They mainly depicted outside views of the churches and details with some specially dressed human figure. Knowledge objectives usually dominate education with little concern in helping young people explore the inwardness of their religious experience (Rawding & Wall, 1991). The arts, with their stress on imagination and personal expression, can help people revitalize their notions of spirituality. Thompson (1979) referred to the “potential in art for helping persons to experience the ultimate, to sense the real and to find meaning in life” (p. 13). Children in particular can learn that pictures are “a way of expressing deep emotions and profound ideas and beliefs” (Duncum, 2000, p. 52). Duncum challenged educators to inspire school children to translate religious events and stories into contemporary conditions. His examples revealed that young children in Australia could respond to the dramatic aspects of the Christmas and Easter stories and their work might exhibit gender differences in form and content.

This ethnographic study explores what some children in Poland represented in drawings of their first Holy Communion, how they developed them, and the significance of the drawings. We describe, analyze, elicit clarifications, and compare drawings as a whole and with findings from other studies on child artmaking (Note 1). We first describe the Holy Communion experience in general, the ritual in Poland, the Corpus Christi pilgrimage and procession as an extension of the ritual, and the school context, related lesson and motivation.

We then analyze the theme, schema, color, and space usage in the drawings. The dominant theme was external church facades. Assessment of children’s use of schema revealed church facades, stained glass windows, and human figures dressed in formal clothing. Their use of color seemed conventionally realistic with no symbolic usage. Examination of their use of space revealed symmetrical arrangements and unique chair perpendicularity to door elevations.

Findings were surprising. Whereas we assumed that the drawings would reveal expressive content—deep religious feelings, we discovered that the drawings seem distanced, safe, and noncommittal. On the other hand, their drawings revealed other aesthetic interests, such as the massive churches and their decorative details.

Conclusions entailed a summary of the aesthetic content of children’s drawings, elements of the event’s uniqueness, a discussion of what was left out of the drawings, and alternative explanations. These explanations include their limited drawing abilities, gender differences—the boys’ concerns with architectural details and the girls’ focus on clothing details, outside influences, power relations, and discussion of the ritualistic role of the ceremony, the essence of Holy Communion, and the essence of their drawings. The young children’s aesthetic experience seemed to be one of “awe” of the physical size of the church and the aesthetic sensory aspects of its details. Critical reflection inspired the researchers to consider their own experience of Holy Communion as adults and the idea of communion in general.

Under future suggestions, we extend the significance of Holy Communion by discussing the humanist importance of “breaking bread.” This entails extra motivation and discussion with children. So what was “special” about their aesthetic as well as religious experience of Holy Communion as evidenced in their drawings?

Art as “Making Special”

Anthropologists have been interested in visual artifacts and their cultural significance but usually not their aesthetic value. In many cultures, although no word exists for art, people make important things and conduct special activities or rites. Dissanayake (1988) argues that art is making something "special" or extraordinary. Her arguments stem from such researchers as biologists Tooby and Cosmides (1990) who distinguished between human adaptations such as making special tools and expression that changes with each context. She also refers to the work of anthropologists such as Turner (1974) who distinguished between ritual and play. She mentions such educators’ conceptions as Gardner’s (1983) spatial thinking and Winner’s (1982) art as cognition—the ability to process and manipulate symbols. Finally, she includes Danto’s (1981) transformation of the commonplace, the ability of art to assimilate the actions of people through co-opting their feelings.

Dissanayake emphasizes art-making behaviors rather than products and explains similarities between rituals and art that include:

- arousing feelings and attention through beautiful and enticing objects,

- using unusual and poetic language and voice, exaggerated movements, repetitive music and actions, and extravagant displays of flowers, clothing, and numbers of performances and people,

- incorporating stylized or formalized actions,

- socially unifying people's moods of joy or fear,

- separating them into another setting such as a museum or sacred place,

- combining symbols with mysterious meanings (pp.47-48).

Dissanayake (1992) cites the ancient Greek concept of rite, dromenon, which means, “a thing done,” a concept earlier employed by the anthropologist Harrison (1913). According to Harrison (1913), “To perform a rite, you must do something, that is, you must not only feel something but express it . . . you must not only receive an impulse, you must react to it” (p. 35). It is this final stage—the children’s reactions on which we want to focus. Maybe this is stretching the point, but if the Holy Communion rite is a powerful, albeit a very special, religious, cultural, and aesthetic occasion, then what do the children draw, say, and record about it?

What is the Holy Communion Experience?

When a child reaches the age of reason, s/he starts to prepare for the rite of Communion offered by the Roman Catholic Church. This rite enables the child to take part in all the church sacraments. The child must have a desire to receive communion and be aware of the church’s basic doctrine. Preparation consists of several days of learning the sacred lore and how to receive the holy bread. Parents help prepare children by sharing bread together as a family and encouraging children to donate food and money to the poor. Parents also explain how bread and wine are made as products of seed and vine, soil, and sun (Cronin, 1995). They talk about the man who fed the poor and healed the sick and fulfilled the biblical prophecies that he would die on the cross and rise again. Children also confess their sins before receiving the sacrament of Holy Communion in the sacred rite of Confession. On the day of their First Communion, a Sunday in May, children attend Mass with their families and receive the bread/host for the first time. They dress in special clothes: boys in suits and girls in white dresses and veils, symbolizing the purity of Mary, the mother of Christ. After mass, families host a communal gathering or party for relatives to celebrate the child’s rite of passage (Cronin, 1995).

What is the Holy Communion Experience in Poland?

In Poland the ritual of Holy Communion is extensive. At the main ceremony, children dress in special garb and follow the procession around the church. The priest proceeds to the altar. Throughout the week, called “White Week,” children attend mass every day and take communion with one of their parents. They may wear their special clothes to school. Throughout the spring season, dress shops in Warsaw feature girl manikins in beautifully laced white dresses with hair crowns and flowers. Radio stations advertise the latest toys for gifts as well. Throughout Poland, first communicants also may make a pilgrimage with their families to the Jasna Gora Monastery in the city of Czestochowa to pray to The Black Madonna (Note 2) or participate in a Corpus Christi Procession, which extends the First Communion experience into June.

The Feast of Corpus Christi in Poland

The feast of Corpus Christi, the body of Christ, is celebrated worldwide (Catholic Encyclopedia, 2002). A procession occurs after the Mass, but in Poland the ritual is very special. We participated in the Corpus Christi procession throughout the streets in Krakow that lasted for four hours. We discovered four altars that were erected at four points in the town and decorated with statues, holy pictures, cloth and flowers. The procession stopped at each altar. The streets were lined with people and crepe paper ribbons and flowers as a barricade. In various windows posters of Jesus or Mary were displayed. The procession consisted of musicians, rows of nuns and friars singing Gregorian chants. Then came women dressed in their regional folk costumes and on their heads were elaborate headdresses suggesting baskets of fruit or vegetables that symbolized fertility. Next came rows of young children—first communicants: girls dressed in traditional white dresses with white veils and boys in black suits. Several priests carrying burning incense followed with the bishop carrying the monstrance, a receptacle that held the bread host, symbolizing the body of Christ. A troupe of boy scouts ended the procession. This mix of music, smells, and visual sensations, including the sparkling vestments and receptacles, sometimes places people in a transcendental state.

Method and Procedure

School ethnography is a systematic study of an educational entity that consists of description, analysis, and interpretation stages (Stokrocki, 1997a; Atkinson & Hammersley, 1994). Smith (1978) advocates that researchers report their evolving logic. Interpretive researchers argue that methodological concerns are choices, procedural guidelines are heuristic and quality criteria are emerging and open-ended (Smith, 1989). Critical interpretation methods can be added later.

In this case, school ethnography involved the study of one school, more specifically one class project. When doing ethnographic research in Poland for three months in a private, non-denominational school, Stokrocki daily observed an elementary teacher in action. The teacher, a Professor at the University of Warsaw, became a co-researcher. We decided to focus our attention on the children’s drawing results from a lesson on their First Holy Communion. The lesson was part of the usual projects that teachers offered during the month of May. Thus the study was exploratory in nature.

Description is a process of reporting the events developed from data that are systematically gathered; in this case by daily field notes, photographs, and informal interviews. The teacher translated his directions into English at the beginning of the lesson. While he interacted with the children in Polish, Stokrocki wrote notes about how the children began their drawings and built their forms. We also asked children to describe the meaning of their pictures on the backs of their papers. The teacher translated them and elicited further comments from the children throughout the study. Later, we noticed that the children’s drawings featured mostly churches. Since Poland is a Roman Catholic country, we wondered about the meanings behind what the children represented and what they left out. In this case, the drawings became the primary data to explore. Examples of description included the children’s initial drawing behaviors and our account of the Corpus Christi procession. Since there is no such thing as pure description, interpretation is always synonymous. The teacher was the main interpreter and co-author of the article and our views limit the study.

The next stage is content analysis, which is a search for repeated patterns, in this case, themes and concepts. Traditional content analysis usually involves quantification with different coders for reliability (Bell, 2001, p. 21). Since we were not interested in examining large numbers of visuals, universal claims nor proximate truth, we relied on ourselves as primary research instruments. The task was to “generate” concepts at this time, not to “generalize” about them. We borrowed some initial concepts, such as use of schema, space, and color from Lowenfeld and Brittain's (1987) developmental research and Wilson’s (1977) ideas on child copying and the perpendicular principle (Wilson & Wilson’s 1982). We accomplished this task by making comments on Post-it notes and attaching them to the drawings. Then we elicited further information from the children and the teacher clarified the children’s artmaking from his perspective. These clarifications are included in the body of this paper. Other concepts emerged throughout the investigation.

Comparative analysis is the interrelation of internal findings, in this case, a perusal of the drawings altogether. We conducted a comparative analysis of all the drawings by laying them out on the floor, and noting commonalties, such as theme, subject matter, and details. The determination of themes was a holistic process attained by repetitious viewing and reviewing of the entire collection of visual representations (Ganesh, 2002, p. 14). In this study, the drawings were mostly external scenes of the church that alluded to the theme of preparing for Holy Communion. We included an external comparison with the literature that is related to children’s drawing (Stokrocki, 1997a). We also invited Anna Kindler, a Polish expert on child development in drawing, to add further comments.

The final stage entailed critical interpretation through an examination of the context, issues that emerged, and interpretations about images that children left out of their pictures. Rose (2001) suggested that researchers examine the context in which the image is created, analyzed and viewed as significant. We therefore participated in some of the Polish communion events, namely Sunday Mass and the Corpus Christi Procession, and were able to reconstruct the context.

A researcher must elicit other interpretations of the event. Elicitation was an open-ended interview prompted by visuals (Collier, 2001). The technique entailed gathering explanations of the meaning of an event from cultural insiders—those who understand the Holy Communion ritual. Elicitation also can be used to detect differences in cross-cultural explanations (Fischman, 2000). We also compared these drawing results of religious events with those of children in Australia (Duncum, 2000). Stokrocki further elicited opinions from a priest and communion director in the United States, arranged for children to draw their First Communion, and attended communion rites in Arizona for comparison, which is the subject of a future study.

Next, we investigated any power relations involved. Rose (2001) argued that researchers regard visual data seriously and examine them in relation to existing power relationships that form school practices (pp. 3; 15-32). We included a short section on what power relations were involved under conclusions.

As we continued to explore the dimensions of this experience and these visuals, we needed to explain the method and issues that encompassed our own interpretation processes. This became a confessional section, an appropriate metaphor, since we are both Roman Catholic. Thus, we deconstructed our authority and added other voices to speculate on the meaning of the Holy Communion ritual. The way researchers see images and how they challenge the power relations and social structures made these methods seem “critical” (Ganesh, 2002).

School Context

The study took place at a private elementary school, called The Creative Activity School (Szkola Aktywnos ci Tworczej), which lies in a wooded suburb about a half-hour outside Warsaw. Wieslaw Karolak, InSEA [The International Society for Education through Art] World Councelor, recommended the teacher Professor Mariusz Samoraj for observation because “he works both at the university and in the elementary school. His knowledge is very practical and realistic. The problem in Poland is that professors and artists don’t like to work in the schools.” Mariusz also teaches at Warsaw University, but mostly works with younger students (5-12 years old) who have art two times a week for approximately two hours (Stokrocki & Samoraj, 2000).

Lesson and motivation. On the Monday, following the month-long Holy Communion ceremonies, Mariusz asked one class of six-year-olds (7 girls and 5 boys) to discuss and draw their First Holy Communion experience (5/15/00). He believed that drawings “bring to life spiritual and traditional values.” Children introduced themselves as Mariusz passed out 18 x 24” paper and crayons. He discussed their experience with them. Children talked about going to church, dressing in their special clothes, and eating a special dinner with their families afterwards. This motivational questioning proceeded for approximately five minutes. Even though Poland is predominantly a Roman Catholic country, religious training usually occurs outside of school. During this two-hour session, children slowly discussed possible ideas among themselves, watched others, and eventually started to draw in pencil first, but mostly used crayons.

Findings

Findings include 1) the church landscape as the dominant theme; 2) church facades, stained glass windows, people figures, and props (crosses and flowers, outdoor shrines) as major schema; 3) symmetrical arrangements for space depiction; and 4) typical realistic color usage. Explanations of these findings follow.

Theme

External church scenes. Most students depicted a church landscape from the exterior (10/12) and only one drawing showed the church interior. Horizontal baselines somewhere in the bottom area of the page were the starting points for the church drawings.

Use of Schema

Church facades. All churches basically were symmetrically rectangular and incorporated a front view and arch-shaped windows (10/12). Boys drew more elaborate church structures than girls did. Several boys started by outlining the church as a huge box that filled-the-page. Jendrek's church drawing, for example, at first seemed rushed and crudely drawn (Figure 1). Upon further analysis, I noticed that the church had four levels. At the bottom were three arched doorways that he colored half-white and half-brown to possibly indicate depth. The next layer consisted of a yellow horizontal façade, topped with two triangular pitched gables, and covered with a red roof. He added a blue rectangular layer with a triangular-shaped roof. The child made each rectangle window a different color and size. The church had heavy black outlines similar to the icons in the Russian Orthodox Church in Warsaw. Five crosses symmetrically sat on various roof levels and a small gray cross-hung to the right of the main doorway. Even two crosses at the top appeared at right angles to the slanted roof. Wilson and Wilson (1982) called this orderly configuration the perpendicular principle.

The girls’ churches by comparison were mostly one-story boxes with two symmetrical quadrant windows. The church depictions resembled a child’s stereotypical house schema that consisted of two eyes and a mouth (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A girl's drawing

Stained glass windows. Six students drew stained glass windows. Four female students divided the windows into a quadrant format of different colors (Figure 2). They copied this structure from their classroom teachers. The lesson on making stained-glass windows from tissue paper was on display in the first grade classroom. Jendrek's windows in contrast consisted of nearly 20 different colored squares (Figure 1). His highest window had three vertical sections with a red top.

People figures. Most students drew people dressed in formal clothing from the front view, but two students (a boy and a girl) drew humans from the rear view. One particularly advanced drawing, for instance, consisted of a father, son and mother (from left to right) in rear view with another front view, female figure (on the far right edge of the paper). (See Figure 3 below.)

Figure 3. Agnies's drawing

Agnies drew figures from the bottom-up. She began by drawing the front-view female person in the right corner of her paper. She started by drawing parts from the bottom-up. She outlined the high heel shoes as upside-down, double “V” shapes. Then she drew thick parallel lines for legs and added a triangular skirt with pink petal flowers and purple color around them. Next, she drew a green rectangular shirt with overlapping collar and a “W-shaped” pocket and brown sash. Agnies then outlined the arm perpendicular to the body, added flesh color, and overlapped green color to suggest the sleeve of the shirt. She finished with the circular head that consisted of blue rounded eyes with black lashes, red outlined lips, and a black “U-shaped” nose. She added the brown hair area to sit on top of the head with some hairlines. She called this figure “the sister who was late.” Agnies next drew and colored the priest from the front view. She outlined his long red tunic, then the thick neck, and finally the face drawn in a similar sequence as the sister figure.

Another example is Agnieszka’s drawing of two girls in their white dresses which consisted of hill- shaped skirts, balloon bodices, long sleeves, and circular heads with halo hairdos and smiling faces (Figure 2). She told me that the figures resembled her Barbie doll that has “yellow hair and wears a long smooth dress, white sweater, white covered shoes and white gloves.” Barbie princess dolls were popular in Poland and girls often played with them in school.

The boys probably regarded the people figures as unimportant. Jendrek’s people schema, for instance, were quite crude in comparison to his elaborately drawn church (Figure 1). His four people figures were outlined with the same smiling face and similar triangular shaped bodies in a row on the bottom of the page. Kajtek also outlined his male figures similarly. When drawing the men from the bottom to the top, he started with the triangular-shaped pants, then the shirt, and finally the arm and fingers as petal shapes (Figure 4). Their outfits suggested everyday T-shirts and blue jeans.

Kajtek was the only child to draw the figure of Christ on the cross (Figure 4). He first outlined and colored the cross in gray. Then he overlapped the cross with a primitive-shaped man using flesh color and added two blue eyes and red drips to represent blood. He neatly arranged three flowers on both sides.

Figure 4. Kajtek's drawing

Extra props. Mariusz asked the children what details they included in their church drawings and they answered windows, doors, chairs, crosses, and flowers. Eight students included crosses in their pictures. Most students drew typical petal-shaped flowers and two students included stereotyped “W-shape” birds. Only one student depicted a dog from the side view.

Use of color. Most students’ coloring was conventionally realistic, depicting the grass as green and the sky as blue. Some students (3/12) colored the sky blue in different directions and one boy used gray to indicate Warsaw’s then rainy season. No blending of colors occurred. Only one child lightened colors by heavily coloring white over green probably to indicate the lace covering of the girls’ dresses (Figure 2). This use of typical color—blue sky, green grass, is characteristic of the schematic stage of development in most countries (Lowenfeld & Brittain, 1987). We discovered no symbolic use of color, which is so important during the Holy Communion ceremony, so we dropped this category of color usage and its findings as insignificant.

Use of space

Symmetrical arrangements. Paramount in the church facades was symmetrical arrangements as already mentioned. Such arrangements also appeared in outdoor shrines in five drawings. Kajtek, for instance, carefully colored identical flowers on both sides of the cross (Figure 4). Gardens and altars, such as a separate grotto that featured a cross or a statue of Mary, were dominant around churches and along highways throughout Poland (Jablonski et al, 1997). Whereas the depiction of shrines is not numerically significant here, the presence of outdoor shrines was emotionally significant in Poland.

Chair perpendicularity to door elevations. Remarkable was the depiction of objects drawn inside the church of three girls. For example, Agnieszka portrayed the church interior inside the central curved door by arranging five rectangles perpendicular to the arched door that resembled door reticulation (Figure 2). In the center of the door opening is a stained glass door and above that were three “A-shaped” forms that the girl called chairs in simple elevation. Mariusz later told me that she intended them to be pews, albeit perpendicular to the curved door baseline. Wilson and Wilson (1982) called this orderly alignment “the perpendicular principle” in their studies of children’s drawing. Usually children align their figures perpendicular to a horizontal baseline somewhere at the bottom of the page, but in this drawing the alignment is on a curved baseline, which is unusual. This finding is not numerically significant, but the arched structural combination is an unusual configuration. They seemed to have copied this configuration from each other. Wilson (1977) also discovered that children might normally copy or imitate certain signs when mastering drawing as a sign language.

Conclusions and Critical Interpretation

Ethnographic methods can reveal cultural and aesthetic practices that may have universal implications or be significant because of their uniqueness. Following Dissanayake’s (1988) aesthetic guidelines, we reviewed the children’s drawings for aesthetic content. The drawings revealed 1) special places—multistoried churches and outdoor shrines, 2) beautiful and enticing objects notably stained glass windows, billowy white dresses, and flower arrangements and 3) special signs such as crosses as symbols of their faith, and 4) socially unifying moods of joy, as seen in smiling faces. According to Dissanayake (1992) and Harrison (1913) a person must react to a rite (p. 35). The children however failed to show the religious and cultural importance of Holy Communion.

What did the children express? Whereas we assumed that the act of drawing or writing would reveal expressive content such as deep religious feelings, we discovered that the drawings seem distanced, safe, and noncommittal. In contrast, Duncum (2000) presented evidence that children can learn that pictures are “a way of expressing deep emotions and profound ideas and beliefs” (p. 52). His examples, drawn by children who are older (9-12 years old) than the Polish children, revealed dramatic aspects and spontaneous action associated with the Christmas and Easter stories. In his conclusion, he however admitted, “Not all children’s responses could be considered profound” (p. 52).

Such was the case in this Polish class. There was little expression at all, outside of depictions of church buildings and human figures with smiling faces. The children also failed to represent the action of breaking bread and sharing it at the altar. Perhaps the confusion is in the word “drama.” On one hand, people commonly regard drama as highly emotional conflict and spontaneous action. On the other hand, Turner (1974) argued that this is only one end of the dramatic continuum. Drama needs social enterprise or cooperation to sustain its flow, or life is in a permanent state of chaos. It would be so easy to regard this lesson as one of drawing churches alone, but that leaves out the children’s experience of Holy Communion itself, a notable cultural and religious event in Poland.

The children in the Polish class seemed to sustain a more peaceful and cooperative sense of drama as their figures indicate. They hold hands and line up in a row (Figure 1). The drama was in their preparation to enter the church, the setting of the stage. The sheer expectation or sense of awe is the beginning of their private ritual experience.

How did they draw? The Polish children’s drawings also tended to be more “ordered” than the spontaneous drawing of the Australian children (Sarason, 1990). The Polish architecture with its symmetrical arrangements certainly may have intrigued the young children with its overwhelming size, sense of balance, and sensory delights, especially, the stained glass windows. Even crosses or chairs lined in a row and perpendicular to baselines could be considered further evidence of controlled organization. Children showed advanced spatial thinking (Gardner, 1983) in the development of church figurations (Winner, 1982). Multistoried churches and castles with huge towers, multiple portals, and elaborate stained glass windows are prevalent in Poland’s major cities as well as in the highland folk architecture of the Tatra Mountains (Jablonski et al, 1997). Highly ordered drawing may also result from a highly ordered Polish society that continues to struggle to forget Communist straightjacket routines.

How do the children’s age and lack of experience limit their drawing abilities? One explanation is that children at this age (5-7 years old) and schematic drawing stage are generally sign-oriented and may not have developed adequate drawing schema to show action or interaction (Wilson, 1977). Mariusz later asked the children why they left out the figure of the bread—host. They answered that it is difficult to see the altar because there are so many people in church. They said that they know what is happening with the bread. They also find the figure of Christ too difficult to draw and prefer to represent the church and its pretty windows.

How do gender differences affect how children represent this rite? Duncum (2000) noted gender differences in children’s drawings of dramatic religious events. He noticed that Australian boys, for example, were often curious about how mechanistic operations, such as how the Roman soldiers got Christ on and off the cross at the Crucifixion. The girls were more interested in portraying images of the Virgin Mary and angels. Such is the case in the Polish study. The Polish boys’ drawings of churches seemed more varied and detailed than the girls’ church drawings. In contrast, the Polish girls tended to draw more details in their people and clothes than the boys. A probable explanation is that more men in Poland are involved in industrial or construction jobs, while women still make patterned symmetrical clothing and care for children at home. Parents and teachers may communicate more information about building technology to boys than to girls. The result of this is that boys may gain more technical skills at earlier ages (Colbert, 1996). Thus children form their figural and spatial structures differently. Harris (1963) earlier found that when children draw a man (woman) "the sex difference between mean scores favor the girls at each year of age by about one-half year of growth" (p. 240). Colbert (1996) and Mortensen (1991) report that girls from eight to 10-years-old depict more detail and proportion when drawing human figures than boys of a similar age. Gender roles still seem clearly defined in Poland and thus the content of boys and girls’ pictures may also follow the gender divide.

How do commercial and popular culture influence children? The girls in this Polish study tended to depict fancy dresses and talked about commercial influences such as Barbie dolls. Also evidence in the community suggests that First Communion is a popular secular event in Poland. Photography shops exploit the occasion with enticing romantic portraits of children in various poses. Families host elaborate parties and give children gifts, such as stereos and bicycles. The occasion has become a lucrative business. Parish priests find such commercialism problematic, especially the use of video cameras in the sacristy during mass (A. Prajsnar, personal communication, May 4, 2000). They would rather have children wear plain white tunics. Parents, however, still prefer the fancy clothes and parties. Whereas spiritual concerns are personal, religious ones are institutional. Besides the church, the market and the media seem to influence children and families for the ritual of Holy Communion.

What power relations were involved? Children in Poland now have freedom to depict what they want. The reflective lesson was not conducted in a Sunday school preparatory class or a parochial school. Hence no person controlled the children’s representations. Such responses were “typical of children free to explore the meaning of the stories [and experiences] without the imposition of a holier-than-thou attitude” (Duncum, 2000, p. 52).

What is the ritualistic role of the First Communion ceremony? With such a rich cultural legacy surrounding Holy Communion in Poland, it is surprising that the Polish children failed to represent the social importance of Holy Communion, which is bread sharing. It could be that the experience of receiving Holy Communion for the first time, amid all the pageantry and expectations, is overwhelming, therefore the children resort to safer and simpler depictions. Holy Communion as a rite of passage consists of phases of separation, transition, and incorporation (Turner, 1974; van Gennup, 1908/1960; Stokrocki, 1997b). During the period of separation, religious trainers physically remove the children from the church and its rites into a special place. In the transition phase, children become equal socially as they undergo the trials of learning the sacred lore. Eventually they return for the rite of incorporation or reunion with their community and family, a time of admiring sacred objects and sharing food and gifts. The church’s role is to assist children in understanding the sacred lore and their rights and responsibilities regarding this information. The church is the place where children undergo this change in status. The literal and emotional crossing over the church’s threshold through the door is a momentous event, which the children were picturing. The children are detached from the initial experience, a requirement for aesthetic experience. Thus their emotions are transfigured or numbed by this event. Children have learned to look at their church structure and experience in a different way. Danto (1981) reminds us that looking at a work of art requires learning to appreciate it. Thus, children learned the names of church objects and the idea of community as holding hands with others.

What is the essence of the Holy Communion experience?

Essential to the Roman Catholic faith is Holy Communion, the celebration of Jesus Christ, his body and blood, soul and divinity, under the appearance of the Eucharistic bread and wine. At the Last Supper on Holy Thursday, Jesus took bread and said, "This is my body, take and eat it." Then he took the wine and said, "Take and drink this [wine] which is the sign of the new and everlasting covenant," the bond created by Jesus between God and people (Dietzen, 1997, p. 165). Then Jesus added, "Do this in memory of me" (p. 170). During the Mass, the priest unites the broken bread by dipping a piece in the wine, symbolizing Christ’s Resurrection. The transformation of Jesus into bread may be confusing to outsiders, but Roman Catholics consider it a sacred mystery. Children at this age still may be too young to understand this concept.

What is the essence of the children’s drawings? A final and most significant interpretation concerns children’s meanings. Children often show the “bare essence” of what they have learned, depending on the task and their intentions (Kindler, 1999, p. 336). The young child’s aesthetic experience of First communion may be one of “awe” of the physical size of the church, its sensory details, and related ritual clothing. The children have reconstructed an extraordinary building, its arresting objects, and the environment that is a literal transformation of the common place (Danto, 1981). Their religious or spiritual experience may be immature, but their aesthetic readiness seems very keen as revealed in their drawings of churches and portrayed details. The children learned about the external accoutrements and the repetitive and distanced nature of the Communion ritual, but not about the emotional and spiritual aspects.

Methodological Reflection: A Confession

Critical methodology demands that researchers interrogate their theoretical, and in this case their religious or spiritual, perspectives. We were surprised by the lack of imagery denoting the children’s relationship to the altar or bread. Stokrocki experienced this distanced view when she attended Sunday mass in Poland. Because the churches in Poland were packed with people, practically no one could see the altar. Even in the new churches in Poland, altars still face away from the people. She wondered if this stance added to her sense of mystery or created more distance from the important event—the transubstantiation of the Eucharist. She was overwhelmed also by the beauty and size of the churches and their elaborate details. This study inspired her to review her religious and spiritual convictions. Interpretation was a laborious task, yet educational, as both researchers expanded their ways of seeing. More research is needed on children’s aesthetic, spiritual and ritualistic understanding.

Future Suggestions

Teachers can intensify the communal meaning of such a ritualistic experience with a reflective activity, such as verbal and visual storytelling. This means that the aesthetic experience as Dewey (1934/1980) points out is one of making something and reflecting on it. If teachers desire students to draw certain aspects of their religious rituals, such as feelings or the sharing of bread, then they need to be more precise in their directions. For example, they should tell the story of the Last Supper. They may even need to motivate with famous art examples, such as Leonardo’s or Dali’s paintings of The Last Supper (Note 3). Changing the drawing location or even time of the day may reveal different results.

Teachers also need to discuss the ritual of Holy Communion and its humanistic importance with children. Apart from its complex theological aspects, the humanistic message of Holy Communion is to share. Whenever people come together for the first time, they may share bread. Artist and educator Professor Wieslaw Karolak explained that he begins his summer art institutes in Poland with a bread-sharing rite to unite participants (Note 4).

Although children in the United States rarely eat fresh bread (Note 5), children in other countries delight in its sensory experience—its aromatic smell, warm temperature, its grainy texture, and its sweet or sour taste. In many cultures, families celebrate their communion through bread breaking, whether the occasion is a Jewish Seder, a Turkish-Alevi meal, or a Christian Mass (Note 6). Thus people can share humanistic and aesthetic values regarding communion, no matter what their religion or aesthetic tastes.

Notes

1. This visual anthropology study is part of a larger exploratory study (Stokrocki & Samoraj, 2000).

2. The Black Madonna is an old painting, not a figure of the black or brown race. For information see http://www.christusrex.org/www1/apparitions/pr00002.htm.

3. The sculptor, Marisol also constructed a 3-D version, entitled Self Portrait Looking at the Last Supper (Art Image Publications 2000, p. 23, 1-800-361-2598; #6.17).

4. Thanks to the children and teachers at the Szkola Aktywnos ci Tworczej; my cultural advisors Jerzy, Elzbieta, Anna & Piotr Prajsnar; Katryna Koziol; and Anna Kindler, Associate Professor of Art Education at University of British Columbia.

5. For comparison, I watched two classes of children in a Sunday church school in Apache Junction, Arizona draw their Holy Communion experience as well. Results of this analysis mostly featured the priest, the altar and its related ecclesiastical objects and figures of standing or sitting children. This experience was different in that the priest invited the children to participate at the altar rather than from a distance.

6. Different sects of Christianity share the communion bread in different ways. Whereas the Roman rite uses the wheat host, other sects actually dip small pieces of bread in wine. Still others tear a piece of homemade bread from a larger loaf and pass it around to signify their unity.

References

Atkinson, P. & Hammersley, M. (1994). Ethnography and participant observation, In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.). Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 248-261). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Bell, P. (2001). Content analysis of visual images, In T. Van Leeuwen & C. Jewitt (Eds.). Handbook of visual analysis (pp. 10-34). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Catholic Encyclopedia (2002). Feast of Corpus Christi. Retrieved August, 1, 2002 from http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/o4390b.htm.

Colbert, C. (1996). Issues of gender in the visual arts education of young children, In G. Collins & R. Sandell (Eds.). Gender issues in art education: Content, contexts, and strategies (pp. 60-69). Reston, VA: NAEA.

Collier, M. (2001). Approaches to analysis in visual anthropology, In T. Van Leeuwen & C. Jewitt (Eds.). Handbook of visual analysis (pp. 35-60). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cronin, G. (1995). How to prepare your child for first Eucharist. Video recording. Croton, NY: Ikonographics.

Danto, A. (1981). The transfiguration of the commonplace. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Dewey, J. (1934/1980). Having an Experience. Art as Experience. New York: Pedigree.

Dietzen, J. (1997). Catholic life in a new century. Peoria, IL: Guildhall Pub.

Dissanayake, E. (1988) What is art for? Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Dissanayake, E. (1992) Homo aestheticus. New York: The Free Press.

Duncum, P. (2000). Christmas and Easter art programs in elementary school. Art Education 53(6), 46-52.

Fischman, G. (2000). Imagining teachers: Rethinking gender dynamics in teacher education. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Ganesh, T. (2002). Educators’ images of high-stakes testing: An exploratory analysis of the value of visual methods. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA, April 4, 2002.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Harris, D. (1963). Children’s drawings as measures of intellectual maturity. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Harrison. J. (1913). Ancient art and ritual. New York: Henry Holt.

Jablonski S., Jablonski, K., & Fijalkowski, W. (1997). Poland. Warsaw: Festina.

Kindler, A. (1999). “From endpoints to repertoires”: A challenge to art education. Studies in Art Education, 40(4), 330-349.

Lowenfeld, V., & Brittain, W. L. (1987). Creative and mental growth (8th edition). NY: Macmillan.

Mortensen, K.V. (1991). Form and content in children’s human figure drawings. New York: New York University Press.

Corpus Christi altars. (n.d.). Retrieved August 1, 2002, from http://www.suba.com/~gunkel/corpus1.htm.

Rawding, M., & Wall, B. (1991). Art and religion in the classroom: A report on a cross-curricular experiment. Journal of Art and Design Education, 10(3), 293-306.

Rose, G. (2001). Visual methodologies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Sarason, S. (1990). The challenge of art to psychology. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Smith, L. (1978). An evolving logic of participant observation, educational ethnography, and other case studies, In L.S. Shulman (Ed.). Review of Research in Education,6 (pp. 316-377). Itasca, IL: I.E. Peacock for the American Educational Research Association.

Smith, J. (1989). The nature of social and educational inquiry: Empiricism versus interpretation. Norword, NJ: Ablex.

Stokrocki, M. (1997a). Qualitative forms of research methods, In S. La Pierre & E. Zimmerman (Eds.). Research methods and methodologies for art education (pp. 33-56). Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Stokrocki, M. (1997b). Rites of passage for middle school students. Art Education, 50(3), 48-55.

Stokrocki, M., & Samoraj, M. (2000). An exploratory study of ceramic activities in a Polish elementary school. Unpublished manuscript under review.

Thompson, N. (1979). Art and the religious experience, In G. Durka & J. Smith (Eds.). Aesthetic dimension of religious education. New York: Paulist Press.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1990). The past explains the present: Emotional adaptations and the structure of ancestral environments. Ethology and Sociobiology 2, nos 4-5; 375-424.

Turner, V. (1969) The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Turner, V. (1974). Dramas, fields, and metaphors: Symbolic action in human society. Ithaca: Cornell University.

van Gennup, A. (1908/1960). The rites of passage. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Wilson, B. (1977). Iconoclastic view of the imagery sources on the drawings of young people. Art Education, 30 (1), 5-11.

Wilson, B., & Wilson, M. (1982). Teaching children to draw: A guide for teachers & parents. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Winner, E. (1982). Invented worlds: The psychology of the arts. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

About the Authors

Mary Stokrocki is Professor of Art Education at Arizona State University. She is also Vice President of the International Society for Education through Art, the former President of the United States Society for Education through Art, winner of its prestigious Ziegfeld Award, and a Distinguished Fellow of the National Art Education Association.

Mariusz Samoraj is Professor of Humanities at the University of Warsaw, Poland. He started the Creativity School, the Szkola Aktywnos ci Tworczej in Zielonka outside of Warsaw, and is writing a book on the Ecological Green School Movement in Poland.